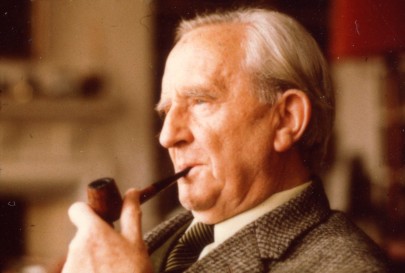

I want to talk about a poem by one of the masters of modern fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien. In fact, Tolkien has been called the Father of Modern Fantasy, as it was his work, especially, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion , that have inspired fantasy writers for the second half of the century, ever since the story of the War of the Ring became popular in the Sixties. In the poem Mythopoeia, Tolkien explains his view of the validity of myth, particularly of the creation of myth, which is what the word “mythopoeia” means. Since it’s so long, I’m going to be breaking this discussion into three parts, with this as the first part.

So, here’s Mythopoeia by Professor J.R.R. Tolkien.

“To one [C.S. Lewis] who said that myths were lies and therefore worthless, even though ‘breathed through silver’.

Philomythus to Misomythus”

First off, we can see from the dedication that the poem was intended for C.S. Lewis, whom Tolkien calls “Misomythus”, or Myth Hater. I’m assuming that this was written before Lewis converted from atheism to Christianity, as he had, before his conversion, been a rationalist, which often denies the validity of myth.

“You look at trees and label them just so,

(for trees are ‘trees’, and growing is ‘to grow’);

you walk the earth and tread with solemn pace

one of the many minor globes of Space:

a star’s a star, some matter in a ball

compelled to courses mathematical

amid the regimented, cold, inane,

where destined atoms are each moment slain.”

I love the beginning of this. Myth is much more than just a lie believed by savages. It’s living poetry that keeps us from being trapped in a cold and inane world where all we are is atoms. With myth, whether organic or created, we become alive, more than someone who simply calls “some matter in a ball, compelled to courses mathematical.”

“At bidding of a Will, to which we bend

(and must), but only dimly apprehend,

great processes march on, as Time unrolls

from dark beginnings to uncertain goals;

and as on page o’er-written without clue,

with script and limning packed of various hue,

an endless multitude of forms appear,

some grim, some frail, some beautiful, some queer,

each alien, except as kin from one

remote Origo, gnat, man, stone, and sun.”

Time marches on, and what are we in the great scheme of things? As we see the world continue, “from dark beginnings to uncertain goals”, we see “an endless multitude of forms.” These forms are the things by which we make our myth, all originating from the “remote Origo”, a term that means, essentially, the origin of all we’re discussing. In this case, the origo of the world.

“God made the petreous rocks, the arboreal trees,

tellurian earth, and stellar stars, and these

homuncular men, who walk upon the ground

with nerves that tingle touched by light and sound.

The movements of the sea, the wind in boughs,

green grass, the large slow oddity of cows,

thunder and lightning, birds that wheel and cry,

slime crawling up from mud to live and die,

these each are duly registered and print

the brain’s contortions with a separate dint.”

As a Christian, it makes sense that Tolkien would proscribe the creation of the world to God, and he imbues in the world a mythic standard. While some of the phrases, like “tellurian earth”, “stellar stars”, and “homuncular men”, are redundant, that may be the point. Myth involves layers upon layers of meaning, and when those layers are redundant, it adds intention, strength, and purpose to them. Of course earth is tellurian, and stars are obviously stellar, but Tolkien’s point is that they are more than just the thing we see. There is a deeper meaning that is not understood through words or science, but through meditation on the nature of what it means to be tellurian, stellar, and homuncular.

As we’ve seen, myth is more than simply stories; it’s the layers of meaning that are hidden beneath the way we view the world. When we create a world of our own, to make it real, we need to do more than simply copy the work of others. Elves, dwarves, and orcs are fine to include. Dragons, chimeras, and gryphons are great. Make them your own. Give them your own meaning, not just something to say, “This isn’t like the rest.” Make it something that is yours, coming from your view of the world, and therefore from your world. Even if you’re not religious, making a living, meaningful fantasy world borders on a religious experience, because it’s drawing from the myth that gives you meaning.